In a society so fixated on one million-dollar word, success—how to be a success, teaching students to be a success, measuring success—the definition has become muddled. Is success defined as money? Fame? Happiness? A promotion? This vague goal hinders action. “Strive not to be a success, but to be of value,” Albert Einstein said. Almost a century later, his message rings true. The best leadership programs of the future must shift their focus away from success to the idea of value. The outcome benefits both the organization and the individual.

Historically, a company’s value was defined by its income statements. Value increased if it made more money than it spent, if it kept a carefully controlled inventory and if it appeared to be growing. Busy offices full of conference rooms and stacks of paper looked like successful endeavors. Selling the widget was the first priority, and the most valuable employees were those who followed the script and generated the most profit.

But then the digital economy emerged, the world got noisy, and the concept of “value” changed. Today, organizational value has become a measurement of how we think, not what we do. Value is becoming a determinant for the types and quality of people an organization attracts. It is becoming an indicator of how quickly an individual can unlearn and learn.

Value skills are not just something organizations can hope individuals will develop over time through experience. This process is too costly and too slow. Rather, the focus should be on creating training and professional development tools that allow employees to practices a variety of situations across a spectrum of organizational challenges.

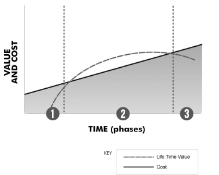

The graph shown above, adapted from the Hay Group, depicts the ratio of value produced by employees to the costs of employing them. There are three phases. Phase 1 represents the time in which someone is just learning a new job. Phase 2 depicts the time in which someone not only knows how to do the job but also does more than what is expected. Phase 3 represents the period in which the job has significantly changed and the individual has not kept up with the changes.

Peter Cappelli, professor of Management at the Wharton School and author of Talent on Demand: Managing Talent in an Age of Uncertainty, observed that over the past few decades, organizations have been finding ways to optimize Phase 2. They minimize Phase 1 by “buying talent” capable of quickly moving into Phase 2 and adding value, rather than investing in training and professional development. This is a great strategy for the short term, but as Cappelli points out, companies offering higher salaries to “buy” talent away from the companies that trained them may be contributing to the unsustainable salary surges seen today.

The logic is that the “buyers” could offer more salary because they didn’t need to recoup the investment that the other company made during the first phase. But when the cycle is recognized, competitors react by increasing salaries internally to avoid losing talent. In the end, both sets of companies can find themselves with very expensive employees who add marginal value.

There are people who are worth their cost, but on the whole, raising the cost line without raising the value line is unsustainable. It adds to the fear, which is part of what causes many organizations to look toward outsourcing, automation, and global partners.

There is another way to proceed: prioritizing learning and talent development within the organization. This is what prompted us to create the concept of the Value Worker—an individual who expands her ability to learn and her capacity to add value beyond the job description.

But how will the best leadership programs develop these workers’ talents? Instead of trying to “boil the ocean” by creating huge catalogs of courses, following unwieldy competency models, and jumping on the next technology bandwagon, a more prudent approach is to focus on the three skills that generate (or impede) value: decision making, problem-solving, and collaboration. More on these three values in posts to come.

Michael Vaughan is the CEO of The Regis Company, a global provider of custom business simulations and experiential learning programs. Michael is the author of the books The Thinking Effect: Rethinking Thinking to Create Great Leaders and the New Value Worker and The End of Training: How Business Simulations Are Reshaping Business.