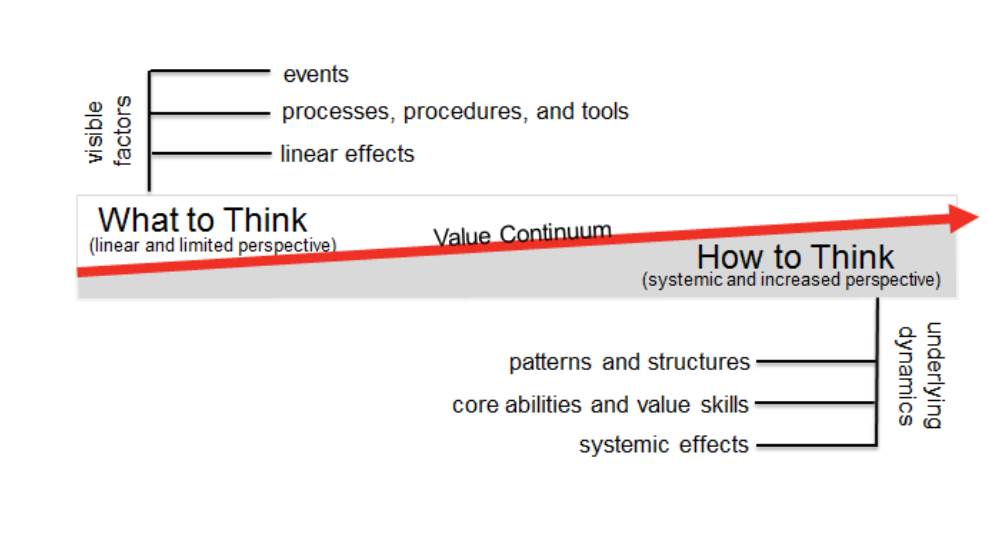

As I’ve noted in previous posts, creating hundreds of professional development training programs over the past two decades has led to the conclusion that there are two main thinking paradigms from which people approach the world. The what-to-think layer is shaped by events, guided by tasks, and consists of a language that is used to describe parts and causality. The how-to-think layer is shaped by patterns and structures and consists of a language that is used to describe systems and relationships.

Developing only the what-to-think layer will allow individuals to function effectively only in known and predictable scenarios. In those situations, their performance may be exemplary. But without attending to the deeper level of how to think, these individuals will be unable to translate their skills to new, unique, and complex tasks.

The reason many leadership development training programs consistently fall short of their promises is because they focus on visible factors, such as outcomes, emotional reactions to a situation, or aggregated data. They address these visible factors by overlaying processes, tools, and procedures that reinforce the what-to-think mentality. The irony is that when processes do not produce a change, our tendency is to add more rules and policies and their accompanying metrics, expecting these to be efficient and effective solutions to systemic problems.

On the contrary, rules and policies cannot affect drastic change in systemic problems. Instead, they more often lead to the unintended consequence of creating more noise.

I’m not advocating eliminating or even reducing the use of processes and tools. They are critical to the success and safety of many organizations—when used appropriately. What I am advocating is a need to move from simply training people what to think to teaching them how to think. This shift follows the Value Continuum path, as demonstrated above.

The primary reason that leaders should help workers move onto the Value Continuum path is that as employees increase their perspective, they increase their value. Markets, organizations, divisions, and teams are all unremittingly connected. As employees move along the Value Continuum, their ability to solve problems, make decisions, and collaborate across geographical and cultural boundaries improves.

This happens because their perspective and ability to think differently improve. They move from seeing the world as discrete parts to seeing it as interconnected systems. Instead of seeing a problem independently, they understand it plays a role in a complex system of other problems that all interact with each other. As they move along the Value Continuum, employees begin to offer input that takes all these parts into consideration, increasing the overall value of their output.

In our learning and development consulting work, my colleagues and I have seen this happen many times. Individuals come into our business simulations with one perspective and leave with multiple new perspectives. Let’s take a quick look at an individual who participated in our simulation training a few years ago.

The business simulation incorporated one of our responsive models that encapsulated the primary dynamics surrounding the organization’s corporate strategy, external market dynamics, and the typical human factors that contribute to good and bad decisions. The experiential, five-day professional development training program was highly competitive. Within the few first minutes of the simulation, participants sensed that they part of something different than any traditional training experience. Their adrenaline was high as facilitators explained that there would be winners and losers. Adding to the excitement, senior executives roamed the hallways listening in to the impassioned debates and reviewed each team’s decisions and results every night. There were a few nights that we needed to remind the executives that this was a marketplace business simulation and they should not react to their emotions.

When this particular individual first arrived to participate in the business simulation, he was confident and ready to show us his business skills. Day 1 went well for him. Day 2 went even better. However, on Day 3, he drove his team and the simulated business into the ground. He was crushed. His team was crushed. He said he honestly felt that he should be fired, and some of the executives who were reviewing their results shared the same feeling. On Day 4, he and his team spent most of their time together trying to get their heads around what went wrong, because on Day 5 they needed to report out to all their peers.

The simulation training experience affected him deeply. It caused him to rethink his approach to leadership and how he ran his division. Recently, he was promoted to a regional position. While we can’t take credit for his promotion, we do know that we gave him a significant experience that contributed to his new perspective.

There is a great need for business training to evolve in order to produce a deeper impact. Today, many corporate leadership training departments respond to problems by creating a course that addresses the visible factors. Perhaps an organization needs a visible increase in sales. To procure a fast result, the corporation may train employees to follow a streamlined process proven to result in successful sales. But what happens two years later when this process is out of date in the perpetually evolving business environment? More processes? Better tools? The greater approach is to develop deeper learning solutions that address how to think, rather than distilling deep thinking into a few key points.

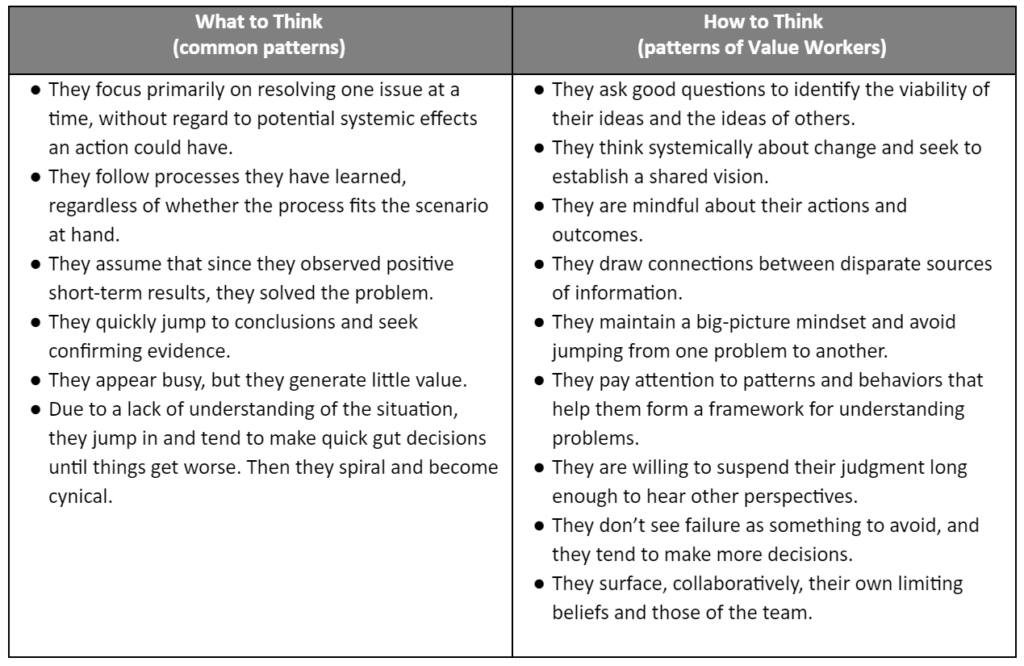

At The Regis Company, we formed an assessment of training based on our observations and data from more than one hundred different business simulation based programs delivered globally. We concluded that the majority of learning and development training provided today primarily teaches patterns of thought that are consistent with what-to-think workers. The participants in these simulations exhibited primarily patterns of thought that are shown below in the What to Think column.

The patterns of thought of Value Workers, shown in the How to Think column, were identified in those participants who performed above average within the business simulations. When confronted with complex challenges and bombarded by noise, the how-to-think participants collaborated effectively and, for the most part, made quality decisions.

In our research, we began to see that these how-to-think patterns of thought, when cultivated via professional development training programs, sustainably improve decision making, problem-solving, and collaboration. We have since organized and mapped the how-to-think patterns to one or more thinking abilities: critical, creative, and systems thinking. We call these the Core Abilities, as they are central to the patterns of thought of how-to-think workers and also to all other learned skills. I’ll dive deeper into Core Abilities in my next post.

Michael Vaughan is the CEO of The Regis Company, a global provider of business simulations and experiential learning programs. Michael is the author of the books The Thinking Effect: Rethinking Thinking to Create Great Leaders and the New Value Worker and The End of Training: How Business Simulations Are Reshaping Business.