About ten years ago, my colleagues and I realized that our challenge as learning and development consultants was to develop a technology that would allow us to model the complexities and the noise that reflects the reality of today’s organizations. After extensive research, we went down the path of business simulations and training simulation software.

If designed and executed appropriately, business simulations:

- Establish meaning and familiarity to provide a rich, contextually relevant environment in which learning can occur

- Compress time and space so that cause-and-effect relationships that would otherwise be lost after long delays can be made immediately apparent to the participant

- Provide an opportunity to observe and record the evolution of decision making, problem-solving, and evaluation processes, and to isolate the relevant elements much more easily than can be done retrospectively with real-world events

- Generate the necessary emotional conditions required to ensure the new learning takes the place of the old learning and replaces inadequate thinking patterns

- Allow for the presentation of multiple scenarios that expose participants to an assortment of situations to adequately identify gaps in their thinking abilities

This led to our most important invention at the time, SimGate™. SimGate is used to design, develop, and deliver learning and development training in all four quadrants, but its primary capabilities are optimized for developing the how-to-think skills and abilities.

Our first simulation training created on SimGate was released in 2004 to MBA students. The “Mercury Shoes” simulation consists of five rounds. Each round represents a segment of time, in which a central processing engine presents a set of increasingly difficult challenges.

The business simulation included recognizing and responding to the impacts of global competition, multicultural human resource management, domestic and foreign government policy, global marketing, product development, and regional trading blocs such as the European Union or NAFTA. The simulation simultaneously accepts and processes hundreds of inputs and provides robust feedback on the impacts that decisions have throughout the system, including those caused by delayed effects.

We used the business simulation to test various hypotheses, all under the belief that as complexity within the system increases, the quality of decision making and the effectiveness of collaboration decreases. We studied team formation and communication, problem-solving, responses to ethical decisions, and leadership dynamics.

The results of the simulation training were truly fascinating. Even when we simplified the simulation by offering only a few decision points, participants learned a great deal about team, business, and leadership dynamics. In one business simulation, a participant asked us for permission to fire his entire team. The facilitator wisely counseled him to try to work with the others to resolve issues and problems.

At the end of the week, when the team completed the round and “closed the books,” the results showed that he had made some seriously bad decisions—completely unaware of his own flawed thinking. As a result, the team asked for permission to fire him. Now that’s humbling!

Business simulations have been most helpful in understanding the limitations that all people have to varying extents when solving complex problems. For example, a common tendency is for leadership and management training participants to fixate on the immediate information within their purview. Even when we provide them with cues into potential future issues or market shifts, they gravitate toward the here and now. Oftentimes, when we ask participants to process their thinking aloud, they firmly believe they’re thinking systemically, but their actions within the simulation training show otherwise.

Typically, when the problem becomes complex, learners fixate on only one part of the problem until things spiral out of control. Then they chalk it up as a good lesson learned. However, they still don’t understand the need to look at the big picture. Rather, they conclude that they chose to focus on the wrong part.

In contrast, great problem solvers seek leverage points that lead to desirable system behavior. They look at the behaviors of the links, or relationships, instead of the outcomes. They don’t try to do one big thing; they make small incremental changes while maintaining a big-picture perspective. They realize that the old adage “the harder you push against the system, the harder it pushes back” is very real in organizational systems.

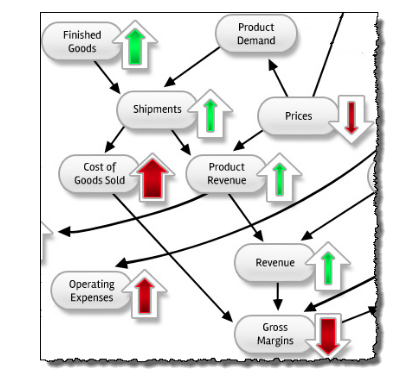

Many of the decision-making simulation training we use with clients include a dynamically generated impact map which is a visual representation of the impact that a collective set of decisions have made on the system and how those impacts interconnect. The impact map shows how a team’s decisions drove key indicators up or down. The size and direction of the arrows show negative and positive impacts as the result of the decisions made by each team. When participants are shown this map during a business simulation, we often observe a behavior we call the “red-arrow syndrome.” Typically, early in the simulation, participants become fixated on the largest red arrow. They jump into problem-solving mode and do whatever they can to change it to green, often at the expense of other parts of the system, which shift to red without much notice.

In the sample impact map shown above, the big arrow next to “Product Demand” drew the undivided attention of a team bent on increasing market share. The team realized only after several rounds that demand was based on a number of factors, including the size of the potential market, pricing and promotions, reputation, services, and responses from competitors. They learned that they could not change product demand without understanding how to drive it systemically.

Watching the map change colors from green back to red gave participants their “aha!” moment. Suddenly, the relationships between the parts of the system and the whole system made sense. During the rounds of training and professional development that followed, the team gradually solved more problems and turned more arrows green or reduced the magnitude of the impact shown by the red arrows. This was an exciting breakthrough for our group of trainers because it gave us confidence that we could actually create real behavioral change.

As I mentioned earlier, it was through business simulations that our team began to recognize the impacts of the derailers. We got to a point where we could select, with some certainty, which teams would do well within the simulation training based on how well they defined team norms, structured decision making, and treated one another. In addition, we observed that participants who exhibited a sense of awareness of their limitations and those of others tended to collaborate more effectively.

The types of questions participants or teams asked gave us insight into those who would do well in the early rounds, where linear thinking was best, and those who would do well in later rounds, when the complexity increased. For example, teams who approached the challenges systemically asked questions like these:

- “How is this happening?”

- “What would change the patterns we are observing?”

- “How would a new condition influence the system’s behavior?”

The most successful teams also established a shared vision and a common purpose. These teams seemed to elicit the patterns of thought that lead to better questioning and collaboration.

As a result of these observations, we started to look at participant behavior in our learning and development training programs over time. The data informed the creation of new design principles and feedback instruments. We now use a design principle called the “emotional throttle” to change team dynamics and participant engagement. By adjusting the throttle, we can influence decision making, collaboration, and a myriad of other human dynamics. For example, simply increasing the amount of information during a round tends to increase team strain and decrease the number of decisions a team makes during that round. Providing too many decision points often prompts participants to resort to guessing, while providing too few tends to cause them to over analyze or become less engaged.

We also used the data from the early business simulations to create new techniques for assessing and providing feedback specific to the Core Abilities and Value Skills. Feedback is essential to help people understand how their actions contribute to the behavior of the systems within which they work. Merely practicing or watching other people’s actions is not enough. Individuals don’t necessarily learn by doing—they learn by understanding what happened based on their actions (or the actions of others). Usually, the two happen together. People learn something and perform an action, and then they observe what happened (or are informed by it). It is through the process of understanding that insights frequently occur.

Unfortunately, this step into understanding is rarely taken, so insights are formed sporadically at best. This is especially true when dealing with a complex system, since inexperienced people tend to skip the understanding phase or fixate on the wrong things. Feeling confused or overwhelmed, people tend to become indifferent to the results and move on to the next action in hopes that luck will be with them and things may improve.

To move people beyond taking chances with luck and into purposeful thinking, we must ensure that learners receive multidimensional feedback during and after business simulations to help them understand their mental models.

Michael Vaughan is the CEO of The Regis Company, a global provider of business simulations and experiential learning programs. Michael is the author of the books The Thinking Effect: Rethinking Thinking to Create Great Leaders and the New Value Worker and The End of Training: How Business Simulations Are Reshaping Business.