A system is a collection of interacting, interrelated, or interdependent parts that form a complex and unified whole that has a specific purpose. Each part of a system plays a role, and the malfunction of one piece can interrupt the flow of the entire system. The concept of systems thinking, both in leadership development programs and society in general, is a way of seeing the world as a confluence of systems—all systems that influence our daily lives, our organizations, and, ultimately, our actions.

Systems surround us. We are immersed in them. Examples of systems can be found everywhere—ecosystems, economic systems, geopolitical systems, societal systems, and family systems. In fact, we are ourselves a complex system of systems.

The world today is intimately and intricately connected, but reductionism is rampant. We are so busy that we reduce complicated scenarios to memorable bullet points and easily definable silos. Given the intricately interwoven nature of our world, this isolated approach to thought is more fruitless and more detrimental than ever.

Compounding the issue is the fact that our brain seems optimized for performing tasks that follow a linear progression. That tendency is probably why reductionist thinking is so prevalent. We are programmed to think this way, so the concept of systems thinking seems difficult. The remarkable truth is that systems thinking is an innate ability; many of us have simply not exercised it. This is evidenced by the remarkable outputs of many of the custom business simulations we facilitate with our clients.

I firmly believe that if we were to teach children to think systemically, their brains would be optimized to think systemically about the world. Not only have I seen it with my own children, but I also witnessed it when I observed six Arizona elementary schools that are part of an initiative led by the Waters Foundation to incorporate systems thinking into all academic subjects.

In one of the schools, 11 students met with a learning and development consultant trained in system thinking for six months to learn habits of system thinkers. These young adults had been deemed by their school to be problem makers and were all likely to be held back due to their dismal grades.

I was blown away when I watched these young people discuss complicated issues and collaboratively come up with solutions. As they discussed school community issues, they recognized how their own actions inadvertently contributed to the problems. They also took on long-term issues, such as environmental planning, in which they could articulate potential impacts 5, 10, and 20 years out. I told my colleagues that these kids would be the envy of many top executive leadership programs. Not only did all their grades substantially improve, but also they were no longer destined to be held back, and many of them joined school programs in leadership roles.

Systems thinking can improve overall thinking whenever people are willing to let go of a reductionist past. For employees to really do their jobs, they must understand how their individual actions and decisions contribute to the larger system. This “big picture” perspective helps employees and organizations attain success.

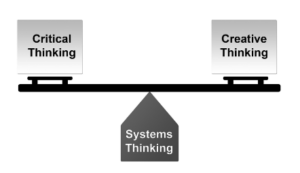

For individuals and organizations alike, systems thinking provides a way to view situations or problems within the context of the larger systems that created them. This viewpoint offers a framework for business simulations that stress critical and creative thinking to produce true insights. If creative thinking and critical thinking are two sides of a scale, then systems thinking is the fulcrum, balancing both creative and critical approaches based on the situation at hand.

Systems thinkers look at cause and effect, relationships, feedback, delays, and unintended consequences to find a balance point. Without the balancing effect, creative thinking can become unbound, and an organization may be distracted by chasing too many ideas. Conversely, organizations too heavily focused on critical thinking can get stuck in the perceived need to analyze too much information, creating the well-known “paralysis by analysis” syndrome.

A typical response in either of these circumstances is to focus on better leadership and management training to solicit new ideas and vetting them. These solutions address the visible factors, but the underlying problem is actually the thinking and attitudes of the workers. Change the thinking, improve the leadership development program, and you change the organization.

Michael Vaughan is the CEO of The Regis Company, a global provider of custom business simulations and experiential learning programs. Michael is the author of the books The Thinking Effect: Rethinking Thinking to Create Great Leaders and the New Value Worker and The End of Training: How Business Simulations Are Reshaping Business.